By Adefoyeke Ajao

It is impossible to speak about the history of theatre – or film – in Nigeria without mentioning Duro Ladipo, who until his death 40 years ago on 11th of March 1978, was an astute theatre manager and industry pioneer. An omission of the celebrated actor, composer, playwright and theatre director would render such an account invalid or at most incomplete and fictitious. This is because Ladipo, alongside his itinerant (alarinjo) troupe, the Duro Ladipo National Theatre, was pivotal to the development of a brand of theatre that not only sought to entertain, inspire and educate audiences regardless of their class or creed but also promoted Yoruba folklore and customs through their performances.

Born on December 18, 1931, to an Anglican preacher, Durodola Ladipo was the first surviving child of his parents – who had lost 13 other children prior to his birth. His parents’ desire to keep him alive earned him the name ‘Duro’ translated as ‘stay’ or ‘wait’ in Yoruba. Due to his involvement with the choral groups in the churches where his father ministered, Ladipo developed an early interest in music and performance. However, in spite of his strict Christian upbringing, Ladipo was enthralled by Yoruba culture and customs and immersed himself in learning about them, sneaking off at a young age to participate in masquerade festivals and rituals to his father’s dismay.

Ladipo’s dalliance with tradition would later influence his perception of the world as well as his art. In 1960, he was asked to compose an Easter Cantata by the All Saints Church, Osogbo and Ladipo, bored by the monotony of Western music in church, decided to experiment by introducing traditional drums into the worship sessions. In an episode of the National Educational Television’s The Creative Person (1967), he described the general reaction to this decision to introduce instruments that were considered ‘heathen’ into a hallowed gathering as follows:

“I said there should be drums here so that everybody will just be happy when they are worshipping. In fact, it was quite strange to the pastor in charge of the church. He didn’t like it, but I just introduced it abruptly one Sunday, putting drums into the songs and [it] was a shock to everybody…”

Undeterred by the outrage that greeted his customisation of the cantata, Ladipo’s work continued to draw parallels between Yoruba mythology and Biblical stories. His penchant for marrying Christianity and Yoruba mythology was evident in some of his works such as ‘Kobidi’, which is based on the story of David and Goliath; ‘Jaleyemi’, an adaptation of Samson and Delilah, and ‘Afolayan’, which was inspired by the story of Joseph. Regardless of the influences on his work, Ladipo’s plays were tweaked to reflect the traditional history and norms and interpolated traditional melodies, poetry and choreography irrespective of the story they were telling. He depended immensely on oral accounts and fine-tuned his narratives by consulting traditional rulers in a bid to understand and accurately interpret his characters.

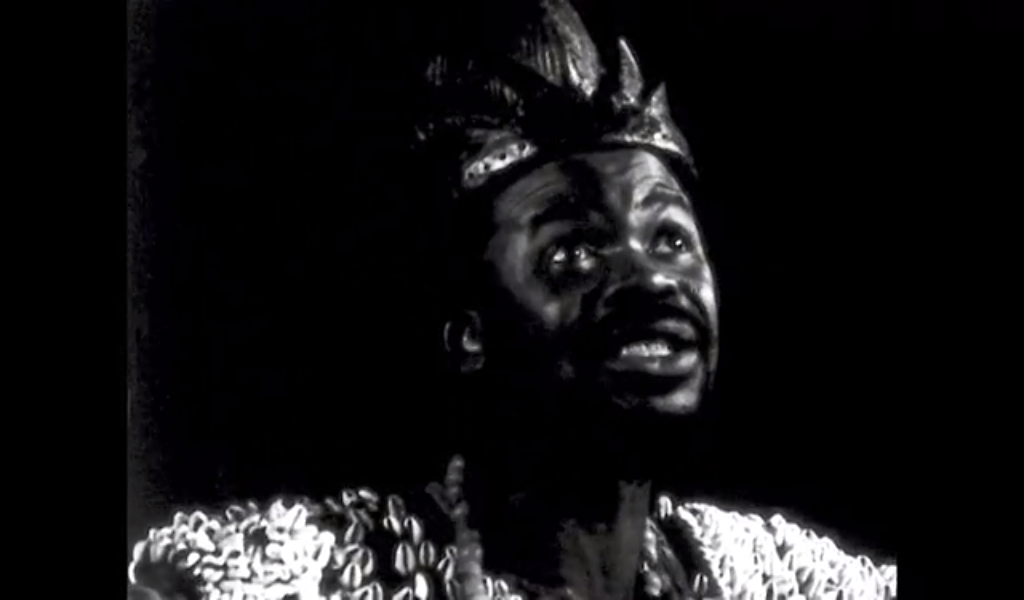

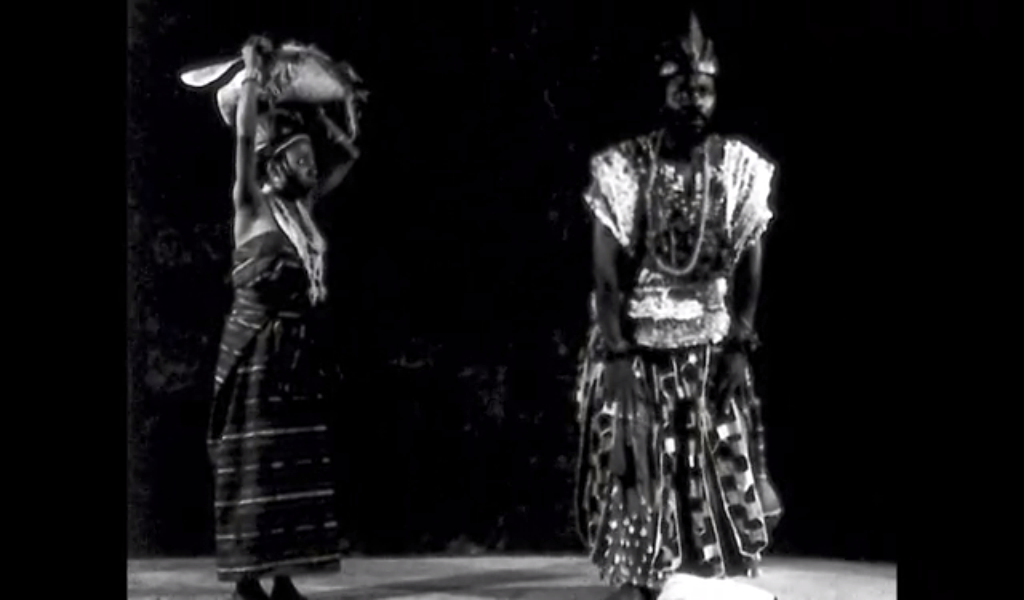

During his lifetime, Ladipo wrote many plays and operas, but his magnum opus is widely regarded as ‘Ǫba Kò So’ (The King Does/Did Not Hang), his 1963 masterpiece, which was based on circumstances surrounding the deification of Sango, the 3rd Alaafin of Oyo who is also regarded as the god of thunder and lightning in Yoruba mythology. Apart from writing this piece, Ladipo also played the lead character with such conviction that not a few people believed he was a reincarnation of the powerful ruler. ‘Ǫba Kò So’ was the second part of a trilogy of historical operas that included ‘Ǫba M’orò’ (1962) and ‘Ǫba W’aja’ (1964). Other historical adaptations for which he was renowned include ‘Moremi’, ‘Obatala’ and ‘Ajagun Nla’ among others. He even explored opportunities in filmmaking with Ajani Ogun (1976) and Ija Ominira (1979). Ladipo’s creative genius did not go unnoticed and due to the global success of ‘Ǫba Kò So’, he received a plethora of laurels which include the Nigeria Art Trophy (1963), first prize in the Berlin Art Festival (1964) and a Member of the Order of the Niger (M.O.N.) in 1965. His commitment to the promotion of tradition also earned him an appointment with the University of Ibadan’s Institute for African Studies.

Ladipo was particular about the impact of his performances on the audience, hence his decision to set up in spaces where people of diverse backgrounds could access his shows. In some cases where there were no functional theatres, the troupe had to improvise:

“…when we get to a town, the first thing we do is to look for a theatre where we are going to play. Many at times there is no stage, we have to make our stage ourselves. We hire empty drums of oil, empty kerosene tins, hire planks, nail them together to get an improvised stage as quickly as we can, and at the same time, we think of lighting problem; we have to use hurricane lantern at times or gas lamp. At times we improvise means by which we can get effects on the stage without electricity. But in many of the towns with electricity, we must try as much as possible [to] get things set ever before we get started with performances.”

The audience was not his only concern as he paid particular attention to other details including acting, effects, costumes and the welfare of his artists whom he placed on a salary to ensure their commitment:

“I started my theatre on a salary basis. I was one of those who started this in Nigeria because I felt people should be tied down to a certain profession. We do everything together and when we go on tour, I feed them and at the month end, I share our profit.”

Ladipo was committed to identifying and developing artistic talent within and outside his company and in 1962, aided by Professor Ulli Beier, he established the Mbari Mbayo Club in Oshogbo. He had, in December 1961, been invited to perform a Christmas cantata at the Mbari Club in Ibadan, and had sought to recreate a similar club in Oshogbo, his hometown. To achieve his aim, he transformed a part of his family home – which used to house a pub known as The Popular Bar – into the cultural hub that allowed artists to develop their talents. This hub would later produce famous artists such as Twins Seven Seven and Jimoh Buraimoh.

To commemorate the 40th anniversary of his passing, Duro Ladipo’s family has lined up a series of events to remember the man whose style redefined the concept of folk theatre in Nigeria. These events will include performances of some of his works, the commissioning of his renovated tomb as well as a fundraising campaign for a new Mbari Mbayo Club in Oshogbo, the town where his creative journey began.

Share

this article 2,860Total views

this article 2,860Total views